Cholera Hits Brockville (1832)

Reproduced drawn map of Brockville 1833, showing Cholera Hospital on today's Blockhouse Island

Cholera is an acute infectious disease of the intestines, acquired by consuming contaminated water or food and causing extreme diarrhea leading to dehydration and kidney failure.

It was brought to Canada in 1832 on ships carrying immigrants from Britain.

Brockville was only just incorporated in 1832, empowered to establish a Police Board.

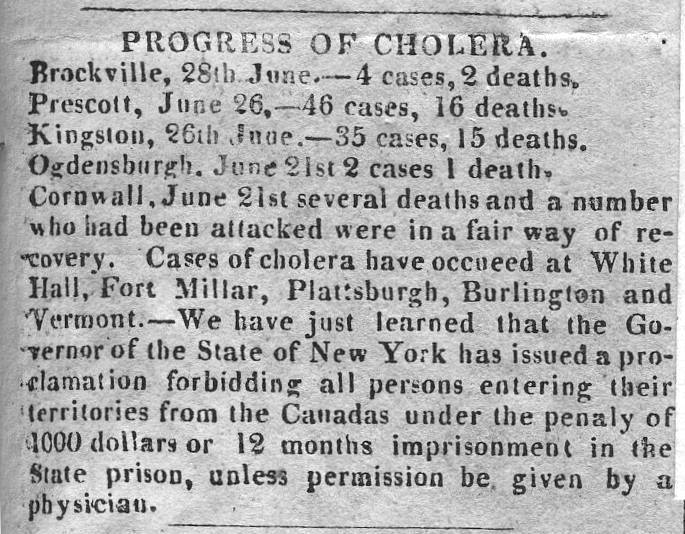

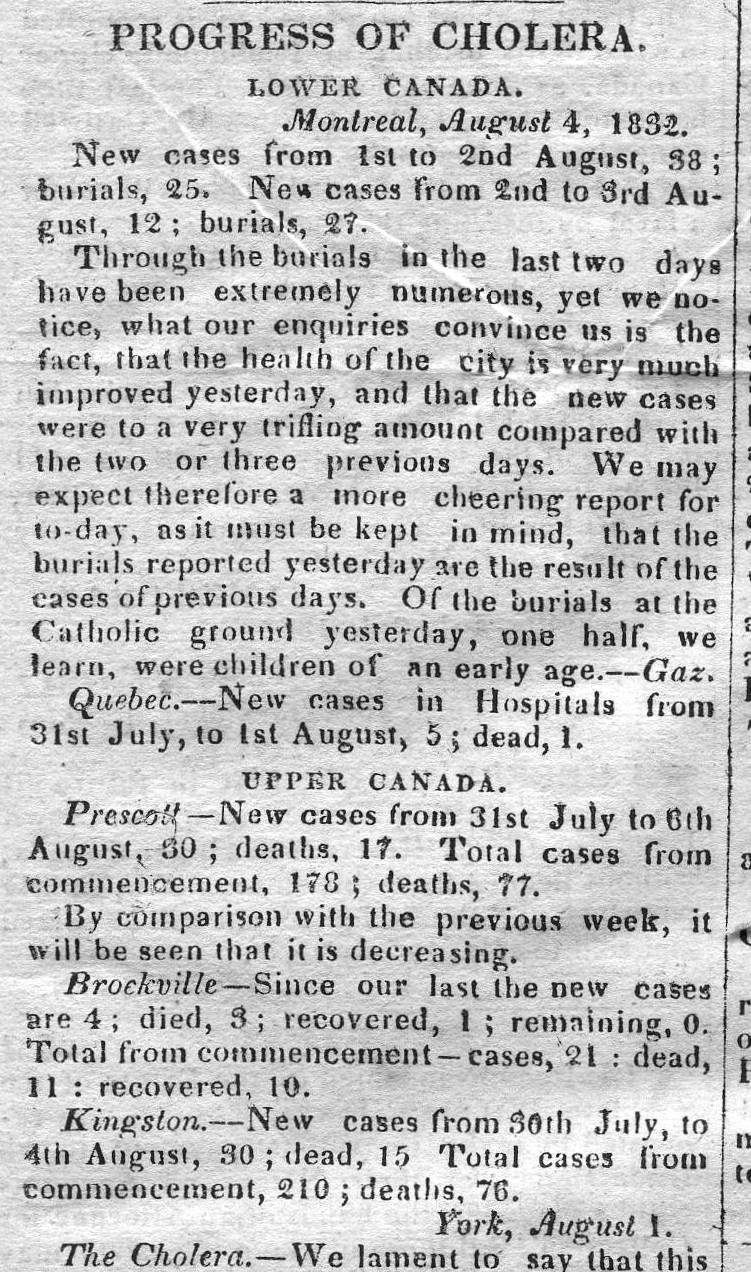

Brockville Gazette: June 28, 1832

It was the newly formed Police Board that was tasked with saving the lives of its citizens. They gathered medicines, beds, and nurses and declared themselves prepared “if it pleases God to visit us with any more attacks”.

The Brockville Police Board appointed Alexander Grant as Health Officer to supervise a team of 11 special constables. The town’s physicians were formed into a Board of Health and directed to visit Brockville homes to ensure that the town was clean.

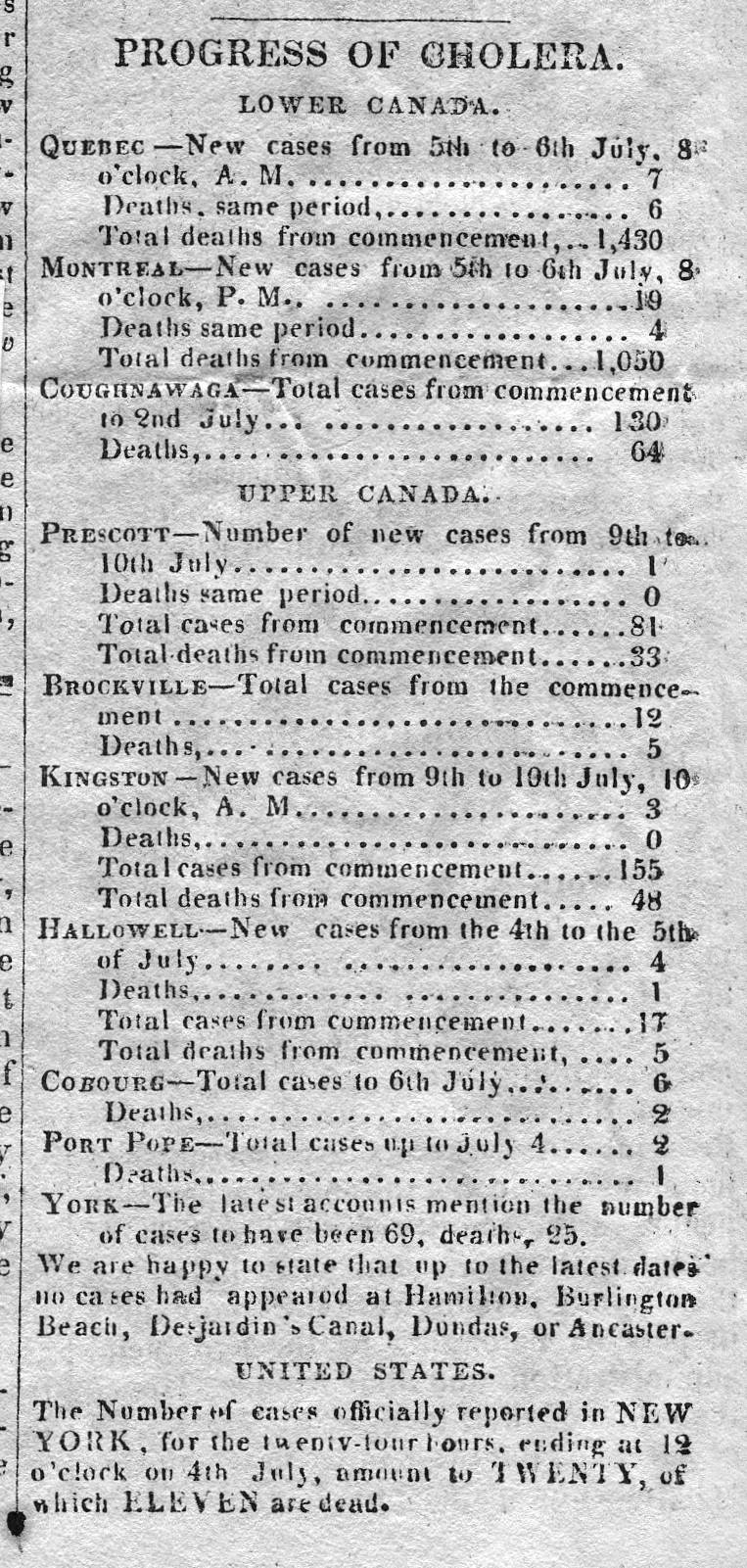

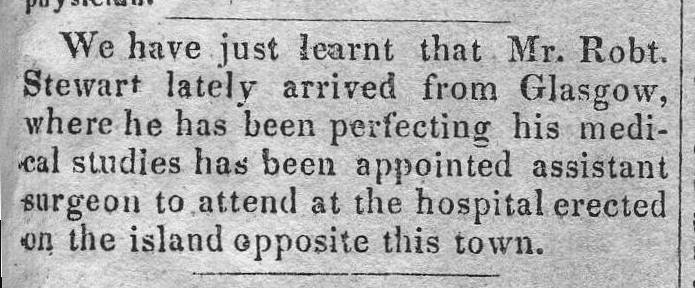

Brockville Gazette: July 18, 1832

Fines were implemented and residents were instructed to make sure everything was clean. Cellars were to be emptied and the walls whitewashed with a “good strong lime” and the fine for not removing “putrid matter, dirt and filth” was 30 shillings.

Brockville Gazette: June 28 1832

A quarantine station was set up on what is now known as Blockhouse Island and sleeping quarters were constructed on the island for doctors.

One of the doctors tasked with tending to the ill, Dr. Gilmour, was one of Brockville’s Cholera victims.

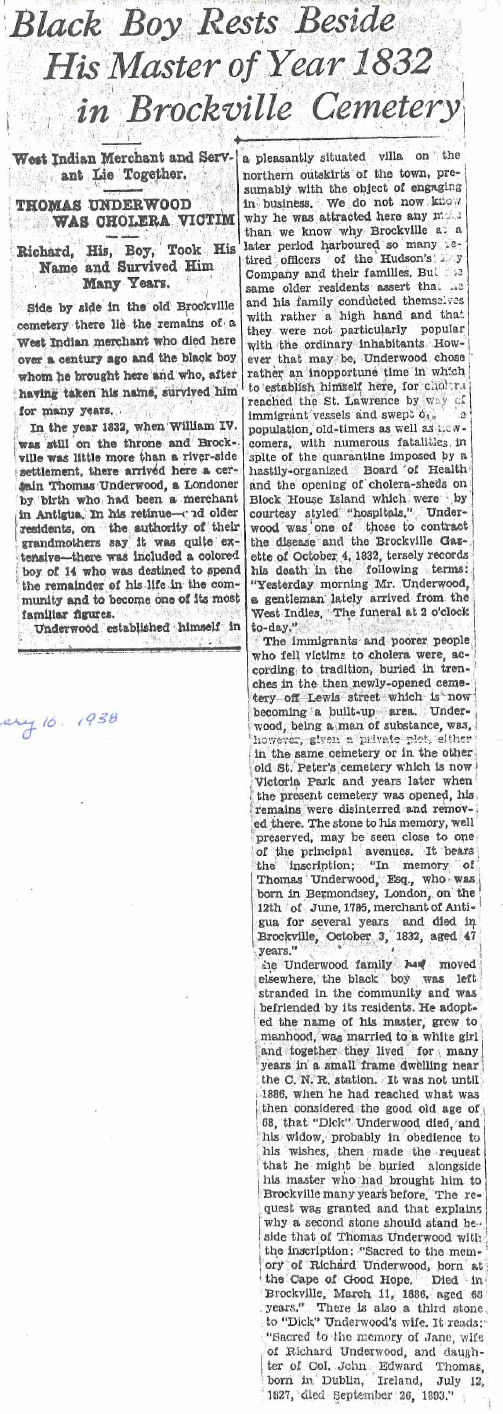

Article from January 10, 1938

Cholera didn’t discriminate between the wealthy and the poor, and like other communities, Brockville was faced with burying their dead, sometimes without ceremony.

This article tells of a well-to-do trader who settled in Brockville just months before the epidemic, who fell victim to the disease. The young slave he brought with him, however, survived, and resided in Brockville until his death in 1886. The two men were ultimately buried together.

Brockville Gazette: August 9, 1832

Brockville emerged from the 1832 having experienced fewer cases and deaths than the busier ports of Prescott and Kingston.

Brockville Gazette: August 9, 1832

Cholera continued to circulate in Canada throughout the nineteenth century.

The Board of Health wasn’t permanently established in Brockville until 1888; until then, the Brockville Police Board would assemble a Board of Health only during emergencies.

By 1906 the Board of Health’s duties included regularly reporting disease, posting quarantine notices, and later, the Board of Health assumed responsibility for coordinating the pick-up of night soil as well as garbage.

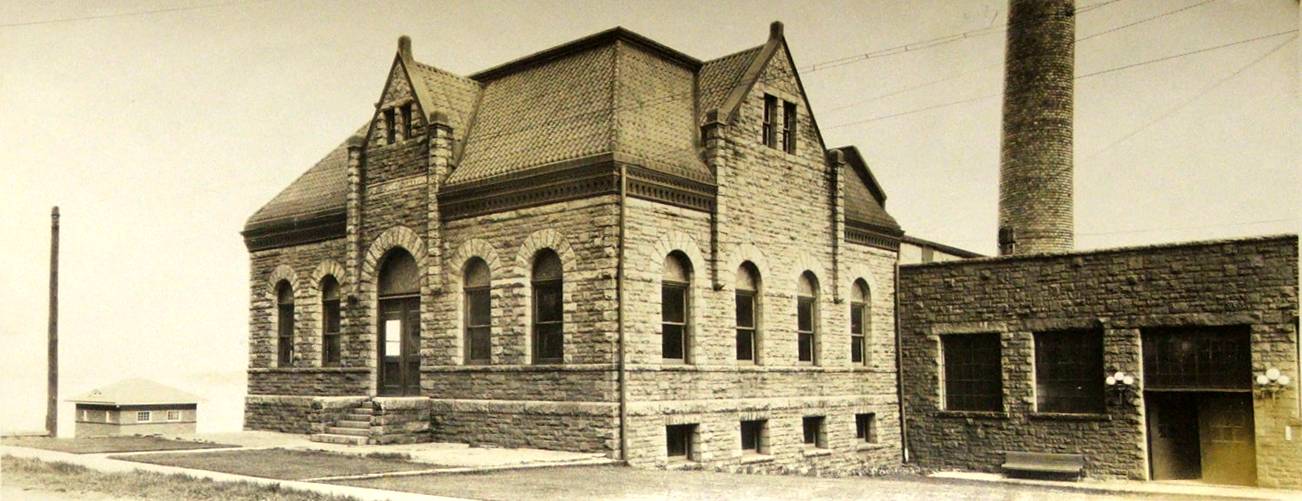

Former Brockville Waterworks

In 1873 it became clear that ground water in Brockville was being polluted by privies, prompting the Board of Health to begin inspecting wells. And like most towns, there was no formal waste removal in Brockville except during epidemics; the only real rule was that no waste could be placed in Courthouse Square. In 1879 residents had to be reminded that winter garbage had to be carried out on the ice past the piers or face a fine.

"New" Brockville Waterworks c1960

In 1892 when the threat of a cholera epidemic re-emerged, residents abandoned their wells and switched to water from the municipal waterworks; but until the “new” waterworks was built in 1960, the only way to ensure “clean” water year after year was to extend the intake pipe further and deeper out into the river.